Canada’s women’s soccer team celebrates its 3-2 victory over Sweden for its first Olympic title at the Tokyo Olympics on August 6, 2021. (Toronto Star, 2021)

Kara Brulotte • Posted: 30-05-2023 | Last Updated: 05-07-2023

Sports are integral to Canadian culture. From sports like soccer played in warmer months to hockey and skiing in the colder ones, Canadians are actively involved in athletics, often from the time they’re young children, with almost 75% of kids involved in sport according to The Physical Activity Monitor (2019-2021). That number decreases as they age, with only 25% of those over 18 years old participating in sport, starting at 44% at 18-24 and decreasing to around 15% for those 65 and older. However, the ratio of those participating also changes throughout the years. For children, 79% of boys participate in sports while 70% of girls do, similar numbers. However, as people age, that difference grows much larger, with only 19% of women over 18 participating in sports compared to 36% of men, almost double. This shows a serious issue with access to sports by gender, specifically professional, and though the government of Canada is aiming for complete equality in sports by 2035, there is still a long way to go. So, what exactly is wrong with the current environment when it comes to women’s sports?

First there is the lack of exposure for women’s sports. According to preliminary data gathered by the Sports Information Resource Centre, 92.6 percent of Canadian media related to sports is centred on male sports, despite the fact that many people desire more women’s sports: 54% of women and 45% of men, according to a study by Canadian Women and Sport (2020). When women’s sports are widely televised, they get views. When Canada was facing off against Sweden during the women’s soccer finals of the 2021 Olympics, the match had 4.4 million views, while the Stanley Cup finals in 2021 only received 3.6 million. The high viewership of the 2021 Olympic Finals show that even though there is a demand for women’s sports coverage, media outlets are still overwhelmingly showing male sports, therefore keeping many female professional athletes from gaining the recognition that they deserve. Women’s sports are not valued equally to media outlets, and that in turn lessens the public’s awareness of female athletes and female sports as a whole.

Players on the Canadian women’s soccer team pose with their gold medals following a memorable Olympic soccer victory over Sweden Friday in Japan. (Loic Venance/AFP via Getty Images)

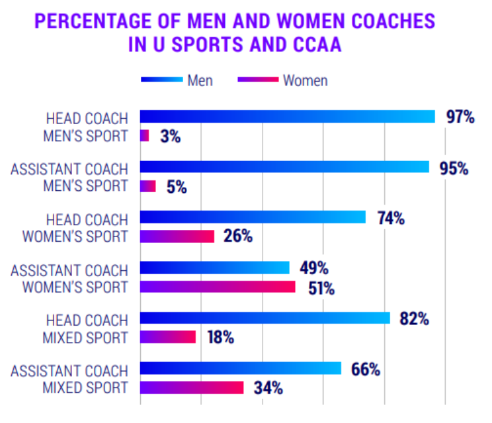

The lack of women in leadership roles in the world of sport, especially among coaches positions, must also be taken into account. In Canadian men’s sports, 97% of coaches are men, while in women’s sports, 74% of coaches are men according to Canadian Women and Sport (2020). The only position of power that women held more than men was assistant coaches of women’s sports. Even then, it’s a 51 to 49 split. Furthermore, at the Olympic level, 83% of coaches were men according to E-Alliance (2021). Thus, there isn’t any mobility for women considering a career in pro-sports, since as soon as they can no longer compete at the competitive level, there is a low chance they will find further employment in the sports industry. Also, having mostly men for coaches can dissuade some women from participating in sports at the professional level. Though this might not faze everyone, having a male coach can be a difficult experience for some. Finally, there is the issue of sexual abuse that occurs at the hands of male coaches. In a study of german competitive athletes who had experienced sexual violence, 63% of the perpetrators were coaches, according to Allroggen et al. (2016). In another study of adults who had participated in organized sports as adolescents and experienced sexual abuse, 78% of the perpetrators were coaches, according to Rulofs et al. (2019). Overall, this discrepancy between male and female coaches makes collegiate and professional sports less viable as a permanent career due to the lack of women in the industry outside of the sports themselves, as well as making a more uncomfortable atmosphere for female athletes.

Gender divide in coaching at Canadian universities and colleges (Canadian Women & Sport, 2020)

Finally, a pay gap exists between male and female athletes, just as it does in other Canadian professions. For example, in 2021 the Canadian Women’s soccer team received around 5 million, while the Men’s team received 11 million according to a statement of operations released by the Canadian Soccer Association Inc (2021), despite the fact that the men ranked 40th and the women ranked 6th according to the FIFA world rankings (men’s and women’s respectively). The women’s soccer team is still fighting for equal pay now, and many other sports show the exact same thing; women being paid less for equal or higher athletic performance. This does not encourage young women to go into professional sports, due to the lack of equal pay and most of all, the lack of equal respect.

What, Why, When and How to Conduct a Pay Equity Audit, 2021

The Canadian sports industry has a long way to go till it reaches equality between genders, and it continues to dissuade young women from pursuing sports after the age of eighteen. In an industry dominated by men, with a lack of media attention and unequal pay, female athletes have a tough break, even outside of simply athletics. However, women have been pushing their way to equal pay, and to equal coverage, and the future of female sports in Canada is bright.

—

Allroggen, M., Ohlert, J., Gramm, C., and Rau, T. (2016). “Erfahrungen sexualisierter Gewalt von Kaderathleten/-innen [Experiences of sexual violence by squad athletes],” in ≫Safe Sport≪: Schutz von Kindern und Jugendlichen im organisierten Sport in Deutschland. Erste Ergebnisse des Forschungsprojektes zur Analyse von Häufigkeiten, Formen, Präventions- und Interventionsmaßnahmen bei sexualisierter Gewalt [≫Safe Sport≪: Child protection in organized youth sport in Germany], ed B. Rulofs (Cologne: Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln).

Canadian Soccer Association, The. (2021). Statement of Operations. https://www.canadasoccer.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/The-Canadian-Soccer-Association-Incorporated-2021.pdf

Canadian Women & Sport. (2020). The Rally Report: Encouraging action to improve sport for women and girls. https://womenandsport.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Canadian-Women-Sport_The-Rally-Report.pdf

Canadian Women & Sport. (2022). Women in Sport Leadership 2022 Snapshot. https://womenandsport.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Leadership-Snapshot-2022.pdf

E-Alliance. [@EallianceSport]. (2021, August 4). #Tokyo2020 is proving that Canada has no shortage of talented female athletes, yet only 17% of coaches in the Games are women. [Image attached]. [Tweet]. Twitter.

Lewis, A. (2021, May 4). What, Why, When and How to Conduct a Pay Equity Audit. RealHR Solutions. https://realhrsolutions.com/what-why-when-and-how-to-conduct-a-pay-equity-audit/

Men’s ranking. FIFA. (1992). https://www.fifa.com/fifa-world-ranking/men?dateId=id13974

Rulofs, B., Feiler, S., Rossi, L., Hartmann-Tews, I., and Breuer, C. (2019b). Child protection in voluntary sports clubs in Germany: factors fostering engagement in the prevention of sexual violence. Children Soc. 33, 270–285. doi: 10.1111/chso.12322

Toronto Star. (2021, August 5). Tokyo olympics day 14: Canadian women’s soccer team wins first ever olympic gold medal; Moh Ahmed wins silver in 5,000m race; Canadian men win bronze in 4x100m Relay. thestar.com. https://www.thestar.com/sports/olympics/2021/08/05/tokyo-olympics-day-14-medal-updates-team-canada-august.html

Women’s ranking. FIFA. (2003). https://www.fifa.com/fifa-world-ranking/women?dateId=ranking_20230324