Lauren Roulston • Apr 22, 2024

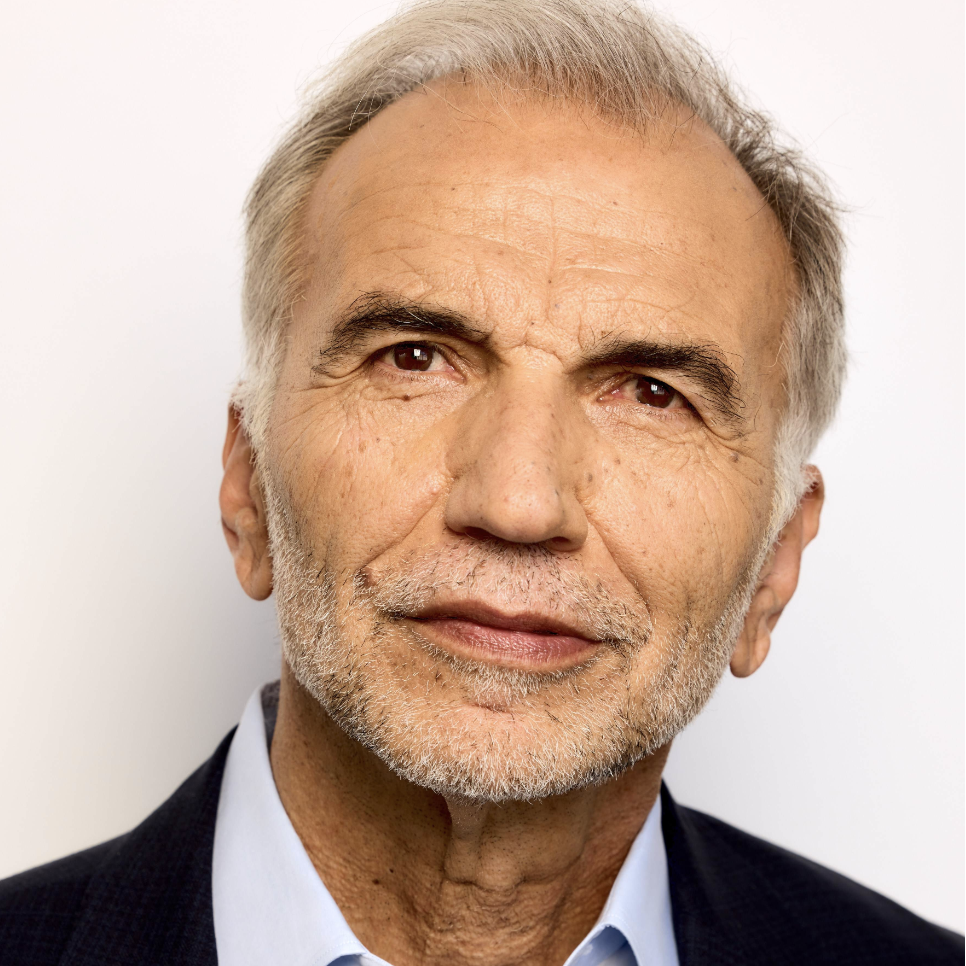

Sam Tsemberis, PhD (uOttawa)

Researcher and psychologist Sam Tsemberis is being recognized for his work combatting chronic homelessness.

He’s currently serving as the CEO of Pathways Housing First Institute and is on faculty at the UCLA Department of Psychiatry.

In the nineties, he developed an evidence-based program called Housing First, which proved that individuals experiencing homelessness must have access to housing before treating other conditions like poverty, addictions, or mental health issues.

Since then his research has inspired policy change across Canada, the United States, Europe and Australia. Last week Time Magazine honoured him as one of its 100 most influential people of 2024.

“In 1992, when Sam Tsemberis founded Pathways to Housing in New York City, people sleeping on the streets and experiencing intense traumas—such as deep poverty, domestic violence, or mental-health conditions—had to prove they were worthy of a roof over their heads before getting help. Sam threw that notion out the window. He listened to people experiencing homelessness, and found that safe and affordable housing was what they wanted first. Housing would provide the foundation needed to receive services and heal what they endured. His model, Housing First, has changed the lives of tens of thousands of people and is influencing policy in cities across the U.S. and the world—from Houston to Helsinki. By treating housing as a basic human right, Sam demonstrated that leading with humanity is the most effective path to ending homelessness.” – Time Magazine

In December, the University of Ottawa also celebrated Tsemberis’ work by presenting him with an award ceremony and an honorary doctorate. Before leaving the capital, we were able to reach him for a call about the ceremony, his research, and the policies he’s inspired around the world.

Here’s that conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

Lauren Roulston: Just to kick it off, congratulations.

Sam Tsemberis: Thank you.

LR: Yeah, can you tell me a little bit about the ceremony that happened on Monday?

ST: Well it was very, what can I say, it was elegant and festive. There was a lot of tradition to it, it was very well organized and had a feeling of participating in something that had years and years of tradition to it, from the music to the ritual.

The president read a very nice speech summarizing some of the work I had done, and then there was sort of the ceremony of the award and then I gave a brief speech and thanks and also on the topic of homelessness and what we can be doing about it.

LR: And when did you find out that you were going to be honoured that way?

ST: Well it was a few months ago, I think.

LR: What was your reaction like?

ST: Well I was delighted, surprised, you know and it was wonderful, actually. I mean, I especially appreciated that it was a Canadian university because I’ve been working in the states for a long time.

But I grew up in Montreal, most of my education was there and I went to college there and I went to graduate school in the states. So, having worked here with a Canadian project called At Home/Chez Soi which was a national study from 2009 to 2014 I worked with a huge team that included people from the university, Tim Aubry, professor Aubry from the University of Ottawa.

Many other people from the University of Ottawa but it was also Toronto and Vancouver, Winnipeg, Montreal and Moncton so it was a national team, and that work had a huge impact not only in terms of the research evidence that it produced but it also changed policy in Canada for the five years following.

So it conjured back to a time where it was incredibly productive and impactful. So it was a reminder of that and also just the leadership of Canadian education researching policy not only nationally here but that study then influenced other countries.

The French did a national study afterwards, and this study still is a seminal study that is referred to in a lot of countries around the globe as evidence or proof of the effectiveness of housing first, you know, so over 100 papers came out of that study.

LR: Wow, how does that feel?

ST: Heh, well when you’re going through it, you know this is huge and important and then after it’s over, the magnitude of it is actually increased because it keeps having influence long after the event itself.

LR: Kind of a snowball effect, do you think if you went back in time and you could tell your past self that this was going to be the result, what would the reaction have been?

ST: That’s an interesting question, I think that this was a study that comes along very rarely in the life of a researcher, you know, it was $110 million investment by the federal government. The vast majority of the money went to services, you know, rent and for housing people.

But the proportion that went to do this study definitely provided the kinds of resources where you could do excellent work, quantitative, qualitative.

So I think we were aware that we were entrusted with a task that was hugely important and I think everyone on the team was very respectful and diligent in producing the best possible work.

I think that if we went back, would we do anything differently? I don’t know that we would do anything differently. As we were going through it I think there was a self-awareness that we’re doing something really important here, and we need to do it well.

LR: And clearly you did, you guys have done excellent work that’s inspired policies across Canada like you said but also in the States and Europe, but before we talk more about the Housing First model, can you tell me a bit about chronic homelessness?

ST: Well, the focus of chronic homelessness is something that is of great concern because it is the group of people among the homeless population that is the most vulnerable.

I mean, even walking around Ottawa today, you know, cold weather, there are people outside wrapped in coats and sometimes sleeping bags that are actually on the street, so it’s not anything where people can comfortably walk by and not notice.

That group, the chronically homeless, are the one’s that public is most concerned about, policymakers are most concerned about, they’re clearly the group among the homeless that didn’t become homeless for a short time and bounce back. They’re still out there.

So they’re more vulnerable, they’re more disabled in many ways, and just providing them with a rent supplement or a place to live wouldn’t be enough, it’s people who need assistance in getting housed, moving to housing and then staying housed.

It’s a group that, if we can’t end homelessness for everyone, they would be the ones you’d want to end homelessness for first, because they won’t survive very long if we don’t. It’s really that urgent.

LR: And helping them out with this housing first model that kind of entails there’s multiple different factors at play so while there may be issues with addictions or mental health or education, those can be aided better along the way but housing is the main issue first. Can you tell me why housing first? Just walk me through that process.

ST: Well, to understand I think it’s important to know what is the alternative, cause housing first is something that was developed as an alternative to treatment first.

Because the services that we have and continue to have, the majority of services for people who are homeless require that the person is sober, is taking medication, somehow in good shape in order to be moved into housing. Based on the belief that they need to be well-organized in order to succeed in housing.

That actually sets up a kind of impossible situation for people to get themselves together before housing. So it was after years of failure of that model that we developed this alternative model, which is let’s house people first and then get them into treatment.

It did require a riskier approach, taking a chance that the person could actually manage housing, even with those conditions that they were facing.

In hindsight, of course, it was absolutely the right thing to do because by providing the housing first, took the person out of that survival mode. They’re on the street where they can’t think of anything else besides, where can I rest? Where’s a safe place to sleep? Where am I getting my next meal? There’s nothing that allows them the energy or space to think about anything else other than getting through the day.

The minute they move into housing, all of that survival mode is soothed. The person is calmer, they’re safer, they’re resting, sleeping in a bed. They’re warm. They can think about other things, they’re not on automatic survival mode.

They’re like, ‘what’s next?’ And ‘how am I feeling, where does my life go from here?’ And of course they have someone knocking on the door and saying ‘how are you doing today?’ And ‘how can I help you?’

So the recovery from both homelessness and other troubling situations happens a lot quicker and a lot better by reversing the sequence and providing housing before treatment. By providing all the supports for treatment after housing.

LR: Right, right. Housing is like a platform for safety and security before launching you into your next endeavour.

ST: Absolutely

LR: So, this Housing First model, it is rooted in the philosophy that all people deserve housing, and I hate to sound pessimistic but today, I don’t know if I see that in a lot of policymakers. Why aren’t we seeing this more prevalent in our day-to-day life? Why are we still seeing so much homelessness?

ST: Well that’s a great question and I think, and maybe it’s naive to assume these things but I think that public policy is driven by political will, and political will is driven by the opinions of the people in the country.

So the advocacy for a right to housing position, I think, is the way to go, because then we wouldn’t be talking about, well, ‘what will this cost?’ And ‘do people deserve this?’ A kind of a, almost a business-model valuing the public policy from a market perspective, which is where policymakers go to if they’re not driven by a social justice mandate to provide, healthcare, for example.

We have a national health plan that took a lot of effort and a lot of advocacy to move in that direction. I think, the battle to end homelessness is in part demonstrating what is possible with programs like the one we’re talking about.

Ultimately, if we want to end it permanently and on a national scale, we have to advocate for a right to housing.

And that’s, you know, that’s an ongoing battle. But we have the evidence, we have the rationale, I think, we need more people to know that this thing has a solution, there’s a solution to homelessness that we need to advocate for and the way to advocate for it is to make it a matter of human right.

LR: And this is a lot of hard work and it can be very heavy and at times, of course, rewarding. But why for you, why this line of work?

ST: Well, I mean, yes it’s a more difficult program than to have something that is a clinic-based program where you go in, people come for their appointment and then it’s five o’clock and then you go home to your life.

But the level of reward and the level of outcomes, you know, the feeling like you’re doing something that’s actually helping people’s lives is not to be underestimated. And I think, also to see that a program that started years ago with 50 people, and now is national policy and helping hundreds of people in different countries is extremely gratifying and reinforcing, you want to do more of it and spread the word, because it really has a positive, huge impact immediately on peoples’ lives.

So, that’s kind of addictive.

LR: Your words are encouraging to hear, do you have anything else that you’d like to add?

ST: I have one thing to add, which is an expression of great gratitude to the University of Ottawa, because when you talk about, you know, the work being hard and what does it take to keep going, I think the kind of ceremony that I participated in on Monday and the joy of that is just so affirming and a wonderful vote of encouragement and confidence to keep going.

LR: Well, thank you so much for taking the time with me.

ST: Thank you, Lauren. Thanks a lot.